Sequencing is one of those learning design decisions that looks “obvious” after the fact… and feels weirdly hard when you’re staring at a blank storyboard. You can have solid content, well thought out activities, and clear objectives and still end up with a course that feels like your lost in the forest. Or worse, you can end up with a a learning experience that just doesn’t meet its own learning goals leaving your learners adrift.

This post is my attempt to make sequencing easier. It’s a practical reference you can use when you’re planning a course, redesigning one that isn’t landing, or trying to explain why your design choices make sense. This can be especially handy when working with SMEs who have deep content knowledge but struggle to see the learning process through the eyes of a novice.

How to use this post

If you just want a recommendation, start with the interactive quick picker (published as a Claude artifact).

If you want the bigger picture, skim the groups and patterns and focus on the “best for” and the examples. Most of the time, you’ll spot a fit quickly.

If you want something printable to share with a team, grab the downloadable comparison chart. This is in Google docs, so you can make your own copy to save.

One important note: most designs use two or more sequences at once:

- A macro sequence – the overall shape of a course or program

- One or more micro sequences – how you structure a lesson, activity, or practice cycle inside the course or program

So in most cases you’re not just looking for one pattern to use. The exception might be micro-courses where you would likely use just one pattern per learning experience.

Sequence pattern groups

I’ve listed the sequence patterns in groups based on learner readiness or autonomy. There are lots of other ways to group these, but I like the learner centred focus that this grouping has.

Treat the groupings as a starting point. Your learners’ background knowledge, the complexity of the content, and the support provided will shift what “fits” where.

More novice-friendly

Works across levels

Best when learners can self-direct

Novice friendly patterns

General-to-Specific (a.k.a. Deductive Sequencing)

This pattern starts broad by introducing key ideas or frameworks, then narrows into details or applications. It’s grounded in Ausubel’s theory of meaningful learning (1968), which emphasizes using “advance organizers” (simple overviews that help people connect new ideas to what they already know).

Best for: New learners, conceptual subjects, or when you want to reduce cognitive load before diving into detail. This is my personal favorite, both as a way to learn and to structure learning experiences for others.

Examples:

- In an AI fundamentals course, you might start with “What AI is and why it matters,” then later move into “How neural networks learn.”

- In a project management course, you could begin with “The project lifecycle: from initiation to closure,” then later move into “Creating detailed work breakdown structures.

Simple-to-Complex (or Hierarchical Sequencing)

Content builds in complexity, following a clear scaffold. Gagné’s hierarchical learning model (1965) underpins this approach, focusing on prerequisites and skill progression. See also Elaboration Sequencing, below.

This ranks as one of my most used models, perhaps because I do a lot of skill-building type design.

Best for: Skill-building or procedural learning.

Examples:

- In a Moodle course, you might first teach “how to create a course shell,” then “how to add content,” and finally “how to track learner progress.”

- In an AI literacy course, you might first teach “how to use a chatbot safely,” then “how to structure effective prompts,” and finally “how to design AI-assisted workflows.”

Chronological or Process-Oriented Sequencing

This pattern follows a natural or logical order of steps, time, or process. It’s useful when the learning maps to a clear workflow, though occasionally it can help to reverse the order for instructional effect (starting with the end in mind).

Rule of thumb: If learners can follow the course while doing the task in real life, you’re probably using chronological sequencing. If you’re thinking of job aids, I’m with you! They are definitely related.

Best for: Training tied to established processes.

Examples:

- If you were designing a research methodology course this could look like: develop question → design study → collect data → analyze results → report findings.

- If you were designing a workshop design and facilitation course, this could look like: identify purpose and audience → plan the session → prepare materials → deliver the workshop → gather feedback and improve

Part-to-Whole Sequencing

This is sometimes called the “synthetic” approach where mastering components needs to come before integration. It’s common in technical training (learn individual software features before building a complete workflow).

This can be challenging for folx who prefer to see the big picture to help the parts to make sense. I’m pretty sure some of my math teachers used this method. It did not work for me.

Best for: Technical training where component mastery is essential, or when parts are complex enough to need focused attention.

Examples:

- In software training, learn mail merge, then advanced formatting, then table creation, then combine all three to produce a complete document workflow.

- Teaching bicycle repair by first mastering brake adjustments, then gear tuning, then wheel truing, before performing a complete bike overhaul.

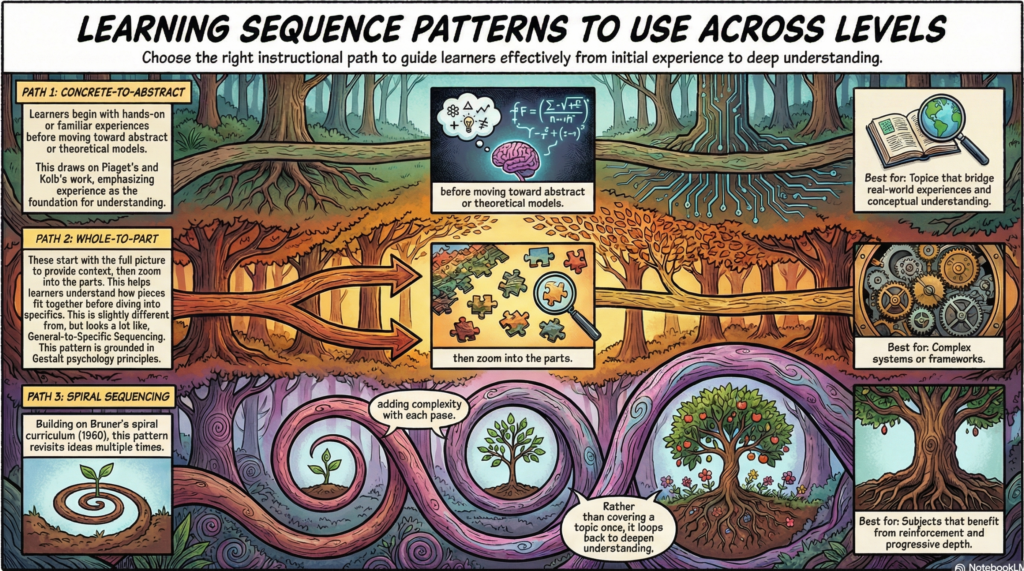

Across levels

Concrete-to-Abstract

Learners begin with hands-on or familiar experiences before moving toward abstract or theoretical models. This draws on Piaget’s and Kolb’s work, emphasizing experience as the foundation for understanding.

I still have nightmares about Kolb’s experiential learning cycle from grad school! But, I do appreciate its value… really.. I do…

Best for: Topics that bridge real-world experiences and conceptual understanding.

Examples:

- In leadership training, participants might reflect on a specific conflict they managed, then identify patterns, then derive abstract principles about conflict resolution styles.

- In an AI ethics course, learners might first experiment with prompting a generative model, then reflect on observed bias, and finally connect that experience to abstract ethical frameworks like fairness, accountability, and transparency.

Whole-to-Part Sequencing

These start with the full picture to provide context, then zoom into the parts. This helps learners understand how pieces fit together before diving into specifics.

This is slightly different from, but looks a lot like, General-to-Specific Sequencing – squinting helps. This pattern is grounded in Gestalt psychology principles. Yes grasshopper, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Or something like that…

Best for: Complex systems or frameworks.

Examples:

- In cybersecurity, you might introduce all six NIST categories first to show the overall framework, then explore each one in depth across modules.

- In an AI governance course, start by showing the organization’s entire AI governance framework (policy, risk management, procurement, training), then break down each component across lessons. Then apologize profusely and give everyone cookies. This can be a high cognitive load sequence depending on the complexity of the topic.

Spiral Sequencing

Building on Bruner’s spiral curriculum (1960), this pattern revisits ideas multiple times, adding complexity with each pass. Rather than covering a topic once, it loops back to deepen understanding.

This is what’s lacking in a lot of private school curriculum imo. I think that most curriculum could benefit from this, even if it’s in the form of reviews and checks for understanding that include past learning. I try to do this consistently in my course design. It can be a hard sell… I’m not sure why…

Best for: Subjects that benefit from reinforcement and progressive depth.

Examples:

- A data science program might introduce statistical concepts in the first term, apply them in different contexts in the second term, then revisit them with advanced applications in the third term.

- In an AI learning pathway, learners might first meet the concept of “AI bias” in Module 1, revisit it when learning about dataset design in Module 3, and return again in Module 5 to examine bias mitigation strategies in deployed systems.

When learners can self-direct

Specific-to-General (Inductive Sequencing)

Here, learners start with examples or cases and then extract general principles. This mirrors constructivist or discovery learning approaches (influenced by Dewey, Bruner, and others) and encourages learners to find patterns and meaning through experience.

Best for: Problem-based or experiential learning when the learning goal is to “understand”, or when curiosity drives engagement.

Examples:

- In an advanced gen AI prompting course, learners analyze several AI-generated texts to discover what makes an output “hallucinate.”

- In a customer service course, participants analyze several customer service transcripts looking for what makes an interaction feel respectful and helpful.

Problem-Centered or Case-Based Sequencing

This pattern begins with a realistic problem or scenario. Learners build knowledge and skills as they work toward a solution. This approach is informed by situated learning and cognitive apprenticeship (Lave & Wenger, 1991). In cognitive apprenticeship, experts model problem-solving thinking out loud, then gradually fade support as learners take on more responsibility.

In this pattern the level of difficulty matters. The problem has to be hard enough to engage and challenge (desirable difficulty) but still achievable. The Kobayashi Maru is not an option, in most cases. This is often used in leadership training, and as a group or team activity.

This is different from the Specific-to-General (Inductive Sequencing) pattern. In this pattern the learning goal is to “do”.

Rule of thumb:

- Choose problem-centered when your learning outcome is performance: apply judgment in a realistic situation.

- Choose Specific-to-General (Inductive Sequencing) when your learning outcome is conceptual: derive/understand a principle from examples.

Best for: Adult and professional learners who benefit from immediate relevance.

Examples:

- A module begins with a data privacy breach scenario, leading learners to explore relevant laws, ethics, and preventative tools.

- In an AI adoption course, learners start with a case where an HR department uses AI to screen applicants. They then uncover ethical, technical, and legal implications while building best-practice checklists for responsible use.

Task-Centered Sequencing

This is based on Merrill’s First Principles of Instruction (2002). While the problem-centered approach touches on this, Merrill specifically emphasizes sequencing around whole tasks that increase in complexity, with learning organized around demonstration → application → integration cycles. Learners watch complete tasks performed, then apply them with support, then integrate them into their broader work.

Remember Grey’s Anatomy? See one, do one, teach one. This is the cornerstone of experiential learning in medicine (William Halsted) and across many other disciplines, from teachers to trades. Scaffolding is usually included to prevent learners from becoming over confident and overreaching.

Best for: Workplace learning where performance of complete tasks is the goal, like removing an appendix.

Examples:

- In teacher training, new teachers first observe, then plan and deliver complete lessons from start to finish, beginning with simple direct instruction lessons, then adding collaborative activities, then differentiated instruction for diverse learners.

- In a course on grant writing, have learners review examples of an excellent grant application, then complete an entire grant application (with scaffolding and feedback), then progressively write more complex grants with less support.

Elaboration Sequencing

This sequence was developed and named in 1979 by Charles M. Reigeluth, an American educational theorist in instructional design. The idea is to present a simplified version of the entire task first (epitome), then progressively elaborate.

This is different from whole-to-part because it emphasizes working versions at each level rather than just context-setting.

This sequence always makes me think of table reads for a movie or theatre. It also makes me think of Agile and Scrum and aiming for the minimum available product.

Best for: Complex integrated tasks where learners benefit from complete working versions at every stage.

Examples:

- A course on website development would begin with a basic but functional one-page site, then elaborating with navigation structure, then adding database integration, then optimizing for performance. (very Scrum-like)

- If you were designing a course on facilitation or meeting design, this could look like: run a short, basic meeting with a clear purpose and agenda → add participant engagement techniques → introduce decision-making or facilitation tools → adapt the meeting for different audiences or constraints.

Choosing the right pattern

Please mix and match these patterns. For example:

- Use general-to-specific sequencing to build conceptual clarity

- Follow with problem-centered activities for practical application

- Apply simple-to-complex sequencing within each task for skill development.

- Add spiral sequencing, especially for longer and more complex learning.

Strong course design usually combines a macro-sequence (the overall flow, like general-to-specific) and micro-sequences (within a module, like simple-to-complex). It helps to keep these micro-sequences fairly consistent so the cognitive load remains where it should be.

Sequencing by learner interest and relevance

This one isn’t a formal sequencing pattern, but it does make every pattern work better: design around learner interest and relevance. It’s closely connected to Keller’s ARCS model (especially the “R” for relevance), backward design, and just-in-time learning.

In practice, this means you can pair almost any sequence with examples pulled from learners’ real contexts including the work problems, scenarios, or decisions they actually care about. For example, you might use a general-to-specific sequence, but anchor each concept in a realistic scenario the learner is motivated to solve. That keeps the learning meaningful and makes the “why” behind each step obvious.

One last thing

Pick the sequence (or combination of sequences) that best fits the content and the learners. Learning happens through relationships: between learner and instructor, learner and content, and learners with each other. As learning designers, we can’t control everything but we can orchestrate the environment and shape the experience. Paying attention to sequence is one of the simplest ways to make learning feel cohesive and to produce better outcomes for everyone.

Here again are the links to the interactive sequence picker and the downloadable comparison chart.

As you can probably tell, I collect learning sequence patterns. Did I miss any? Do you have a pattern not included here? Send them my way!

Create with AI on the side and cross posted to LinkedIn.