Isaac Cruikshank [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Have you even been in one of those meetings where you are discussing the same problem that has been discussed every few months for the past year? You know the feeling. You look at the agenda and you think Oh, for crying out loud. Is this still an issue? Haven’t we made a decision on this yet? Here we go again.?

If you’ve had this experience there is a good chance that the problem has been miscategorized as problem to be solved when it really ought to be viewed as a dilemma to be managed or worse as a complexity to be navigated.

Types of problems

There are many different types of problems. We often forget that and treat all problems in the same way. The problem with equal treatment for all problems is that each type of problem requires a different approach and process. In addition, some problems will never really be solved so setting a goal of solving the problem with a singular solution will only frustrate you and anyone who is trying to help.

Puzzles

The type of problem most of us are familiar with are like puzzles. These may be complicated. Some are really, really, complicated – like rebuilding a car engine – while others can be genuinely simple puzzles like – how do I turn on the printer? With puzzles, regardless of the number of pieces or variables, there is both a clear cause and effect and a solution that will work over and over again, providing the circumstances remain the same.

Sometimes this kind of problem is called an either/or problem. We know there is a solution and it will be either this, or that, or that, or that. The number of thats can be large but the defining point is there is a that?.

Solving Puzzles

Some puzzles are easy enough to solve by an individual or small group. For more complicated puzzles you can bring in experts or lots of people with local knowledge and use trial and error, waterfalls, chunking, brainstorming and other basic problem solving strategies to solve the problem, or series of problems, at hand.

Best or at least good practices are the result of solving puzzles. We do this pretty well and there is a sense ofaccomplishment when we find that perfect solution. Hey mom, I finished the puzzle!

Wicked Problems

At the other end of the problem spectrum we have complexities or wicked problems, as originally defined by Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber. These are problem that are so complex that in order to even understand the problem well enough to frame the question, you need to solve the problem? but in solving the problem, you create more problems. Wicked problems don’t have a clear cause and effect relationship so it’s impossible to find clear solutions.

Wicked problems may be further complexified by disparate values and worldviews. These are problems that never really get solved; rather we run out of time or dollars, chase our tails, or just give up. These are ongoing problems that manifest in unique patterns so best or even good practices won’t work. What we end up are situational solutions that work in one instance and/or only for a short time.

Navigating wicked problems

Dave Snowden suggests we can navigate through complexities using small, safe to fail experiments called probes. The key is to learn from these experiments so you don’t fall into the trap of repeating the same failed experiment over and over again. He uses raising children as an excellent example of a complexity. With complexities and wicked problems, know that you are dealing with complex, organic, interdependent, connected systems and that any movement will eventually cause ripples or waves.

Russell L. Ackoff wrote about complex problems as messes: “Every problem interacts with other problems and is therefore part of a set of interrelated problems, a system of problems. I choose to call such a system a mess.”[23]

Extending Ackoff, Robert Horn says that “a Social Mess is a set of interrelated problems?and other messes. Complexity systems of systems is among the factors that makes Social Messes so resistant to analysis and, more importantly, to resolution.” (source)

Poverty, illiteracy, global warming, homelessness, violence, and addiction are wicked problems that occur at a global scale. Individuals and organizations are probably not going to solve the major complexities of our time, at least not on their own. Some believe that collective intelligence and big data may hold the key to making big dents in wicked problems.

Collective intelligence and diversity?

We can learn to navigate through wicked problems better. Learning to navigate is best accomplished with large and diverse groups of people who have committed to cooperate. Successful navigation through wicked problems affecting us globally can only be accomplished through world communities working together.

What we can do at the individual and organizational level is to manage the symptoms or indicators associated with wicked problems. To do that, we need to be able to identify and manage the associated dilemmas.

Dilemmas

Dilemmas are problems that have two interdependent and known solutions. Dilemmas can seem like wicked problems because they also occur in complex adaptive systems and like wicked problems there is no definitive solution. What makes a dilemma different is that there are known solutions that can be managed well and in that management they can be (re)solved or at least held steady. Dilemmas are still tricky though; when you apply one solution the alternative solution becomes more of a problem.

Managing Dilemmas

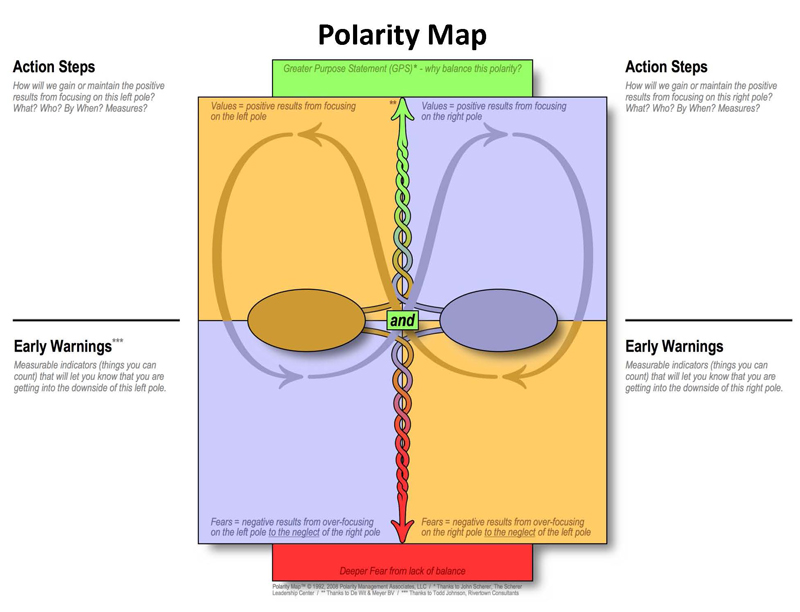

A fundamental question to ask when encountering a challenging situation is: Is this a problem we can solve, or is it an ongoing polarity, paradox, or dilemma that we must manage well

Polarities to manage are opposites which do not function well independently. These seemingly opposing ideas or actions are not customary problems to be solved with Either/Or thinking; they are actually polarities or dilemmas or paradoxes which must be managed with Both/And thinking. Because the two sides of a polarity are interdependent, one cannot choose one as a solution while neglecting the other without experiencing negative outcomes. The point of Polarity Management is to leverage the best of both opposites, while avoiding the limitations of each. (Carolyn McKanders adapted from Barry Johnson’s book Polarity Management)

Polarity mapping

Polarity mapping provides a way to see and manage dilemmas. You know you have a dilemma (aka paradox) that can be managed as a polarity when:

- there are distinct sides – people become polarized

- the problem is ongoing and

- the solutions are interdependent – if you choose one it negatively affects the other

The act of breathing, while it seems pretty simple, is a dilemma that we all manage pretty well.

Problem 1. We need oxygen to survive.

Solution 1. Inhale

Creates Problem 2. We can’t handle too much carbon dioxide.

Solution 2. Exhale

Polarity management

We manage polarities with relative ease, 24 hours a day and seven days a week. On an individual level we manage all kinds of polarities as we try to solve the problem of having a life worth living, being happy, and achieving fulfillment.

We manage polarities like home/work, partner/kids, salad/cheese burger, inhale/exhale throughout our lives. Through trial and error most of us of learn that attempting to maintain one of these solutions to the exclusion of the other, over time, results in more problems. You can also use polarity mapping to manage some of life’s more challenging dilemmas.

Polarity management at scale

Polarity mapping is a great tool for individuals but its real strength is in helping larger groups explore, understand and manage wider reaching polarities. Polarity mapping is a way of seeing and exploring dilemmas at scale. The mapping process allows a group to name their highest values and deepest fears. Fear drives polarized thinking. We allow ourselves to become polarized or in deep opposition to something when we fear losing that something, that we value.

How to map polarities

Polarity mapping works across all sectors and levels (personal, organizational, sectoral, societal) and most importantly it allows us to reframe conflict into sustainable innovation and engagement.

Polarity mapping is best accomplished by diverse groups of people. Bring people into the mapping processes that have a variety of perspectives and opinions about the issue at hand.

In 1975, Barry Johnson developed the Polarity Map a tool that can be used by your group to:

- identify and name the dilemmas as polarities to manage

- surface the positive and negative results of each side

- create a plan that makes it more likely that the positive results of each side will be experienced

- identify early warning signs of slippage into the negative poles

Polarity mapping step by step

With more complicated dilemmas a polarity map can help define the poles and the process of managing them.

Step 1 – Gather a diverse group invested in and committed to exploring the issue. Encourage them to share their perspective or tell their story regarding the issue. Story circles work well for this. You can do this face-to-face or online. Leadership’s role in this is to facilitate the process and hold the space as conveners.

Step 2 – Determine if the issue really is a dilemma or paradox to managed using polarity mapping. Do this a group.

Step 3 – Create an empty Polarity Map. This is a flip-chart paper and marker activity (or post-it) or for those who bend well, a floor with masking tape and cards works great. Write the name of the issue or dilemma to help avoid drift.

Step 4 – Describe the dilemma using the Polarity Mapping tool.

- Start with the fears – what we don’t want. Dig to get at the real and agreed upon wording of the fear. Ask the group to describe the situation they want to avoid. Record this at the bottom centre of the map.

- Next describe what they do want – the agreed upon vision of the ideal situation. Record this at the centre, top of the map.

- Decide on names for each pole. Avoid names that promote bias instead try to use neutral labels. This is the hardest part of this whole process. It requires digging into underlying beliefs and values that are driving the polarization. Here’s some examples of common dilemmas:

- Independence/partnerships

- Freedom/Regulation

- Environmental safety/Economic security

- Efficiency/Inclusion

- Bottom-up/Top-down

- Vision/Reality

- Short-term/Long-term

- Stability/Change

- Candor/Diplomacy

- Tradition/Innovation

- Staff needs/Client or customer needs

- Individual/Team

- Collaborative/Directive

- Agile/Systematic

- Intuitive/Research or data driven

- Value driven/Pragmatic

- Common good/Self interest

- In the bottom left box list the downside of the solution named in that pole.

- In the top left box list the upside of the solution named in that pole.

- In the bottom right box list the downside of the solution named in that pole.

- In the top right box list the upside of the solution named in that pole.

Step 5 – This is where the management begins. Looking at the list of negatives for each pole and determine and record the warning signs – red flags – that could alert you of movement towards this Vicious Cycle. Be specific and detailed. Who will look for these? Is there an early warning system in place? What will we do if we fine ourselves slipping into this area of the map?

Step 6 – Look at the lists of positives for each pole and list the specific actions that could be taken to get to, or remain in, the Virtuous Cycle at the top of the map. Being specific is the key to this. Who, what, when, where, and how will we support and measure these green flags?

An example

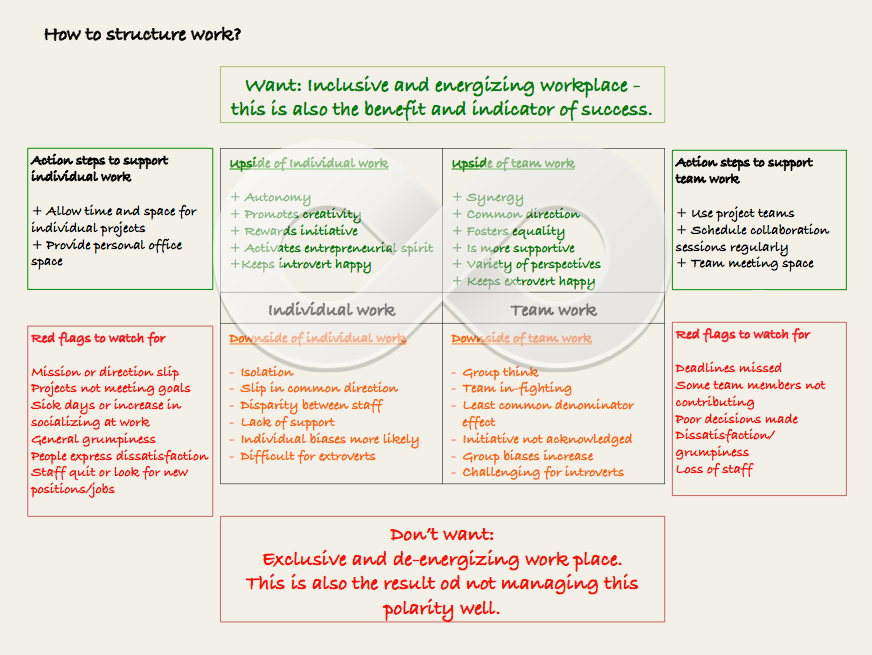

In this example the issue could be called How to structure work?

Again, notice that the outcomes listed as negatives describe problems that are solved by the outcomes listed as positives, on the opposite pole. Problems of working individually are solved by teamwork and the problems caused by teamwork are solved by individual work.

If you look at the issue of how to structure work as a problem that you can solve you may find yourself stuck in either/or thinking and the only route becomes to chose one solution over the other.

If you choose teamwork over individual work eventually biases will emerge, you may lose good people and you run the risk of group think or herd mentality setting in. Yes, it will be easier to collaborate and align to a common vision or goal but the cost will be high.

The solution is to dance between the poles. Breathe in. Breathe out. You can only do that if you identify the issue as a polarity to manage.

Current dilemmas

With the growth of the sharing economy we are seeing new dilemmas arise. Peer-to-peers communities like TaskRabbit, Uber, and NeighborGoods seem to solve problems for many. Airbnb solves the problem of affordable accommodations and offers homeowners a chance to make some extra cash. There are unintended consequences however. It’s effect on affordable housing stock in cities around the world suggests it’s a dilemma that may be best-addressed using polarity management. I suspect the polarities within many of these new sharing services are something like common good/self interest. As city governments scramble to create new regulations I hope they are able to see this as a dilemma to manage rather than a problem to solve.

Right now there are a myriad of problems in every sector that are really either wicked problems or dilemmas. The fields of social housing, education, community development, and environmental sustainability all exist in the complex adaptive system called our world and if we look at the challenges in these systems as problems to solved, we are in big trouble.

So, define your problems wisely – Solve puzzles, navigate complexity, and manage dilemmas.

Parts of this post originally published on the Thoughtexchange blog October 14, 2012

Learn more:

Manage You Polarities or They Will Manage You By Jesse Lyn Stoner

Reflections A Perspective on Paradox and Its Application to Modern Management By Barry Johnson

Using polarity thinking to achieve sustainable positive outcomes

Polarity Mapping – The Leading Teacher

Systems Thinking and Polarities – A Few Basics